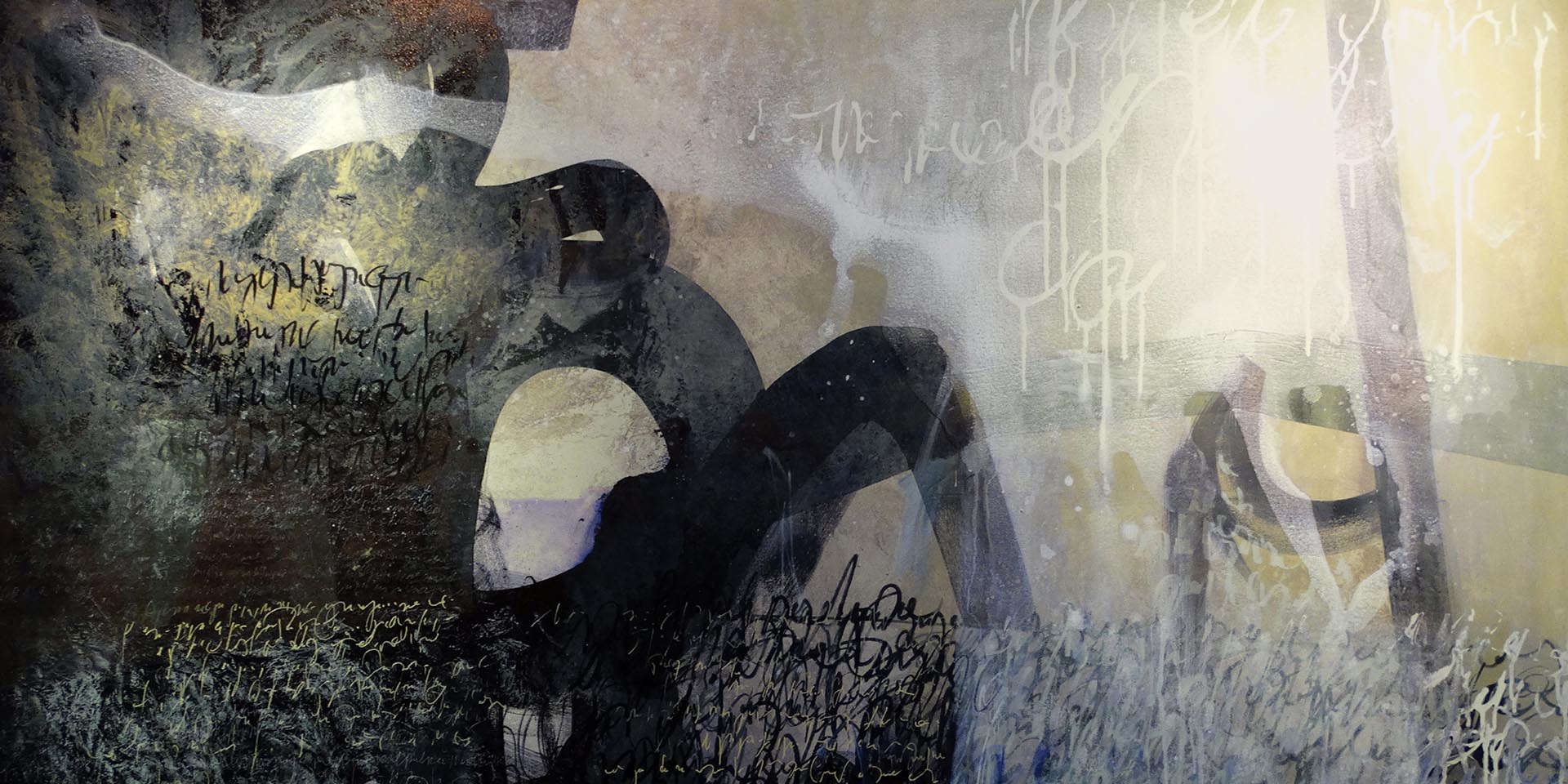

SEMIOGRAPHY. A Visual Experiment at the Intersection of Sign, Language, and Perception | SEMIOGRAFIA. Eksperyment wizualny na styku znaku, języka i percepcji

SEMIOGRAPHY. A Visual Experiment at the Intersection of Sign, Language, and Perception | SEMIOGRAFIA. Eksperyment wizualny na styku znaku, języka i percepcji

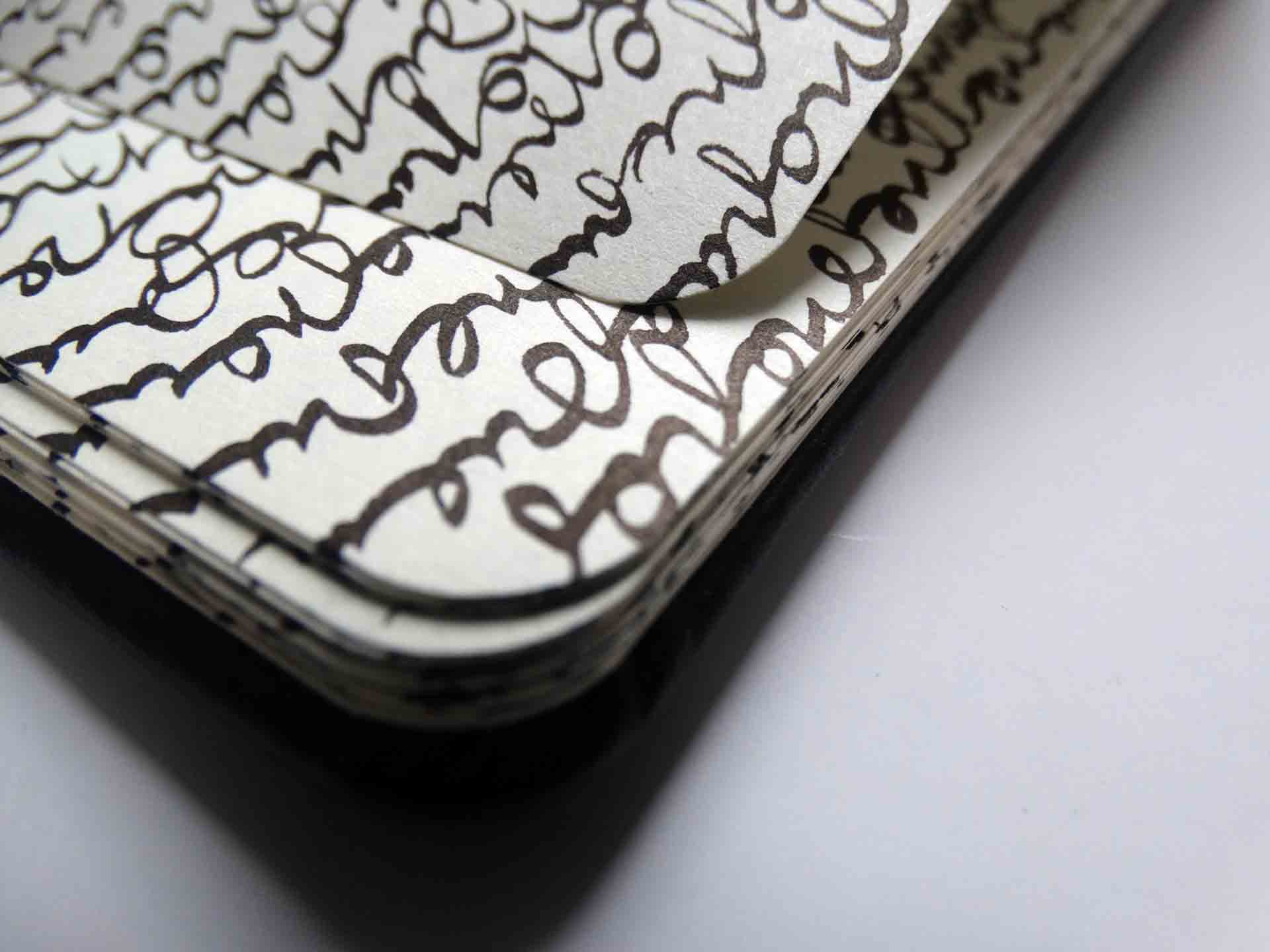

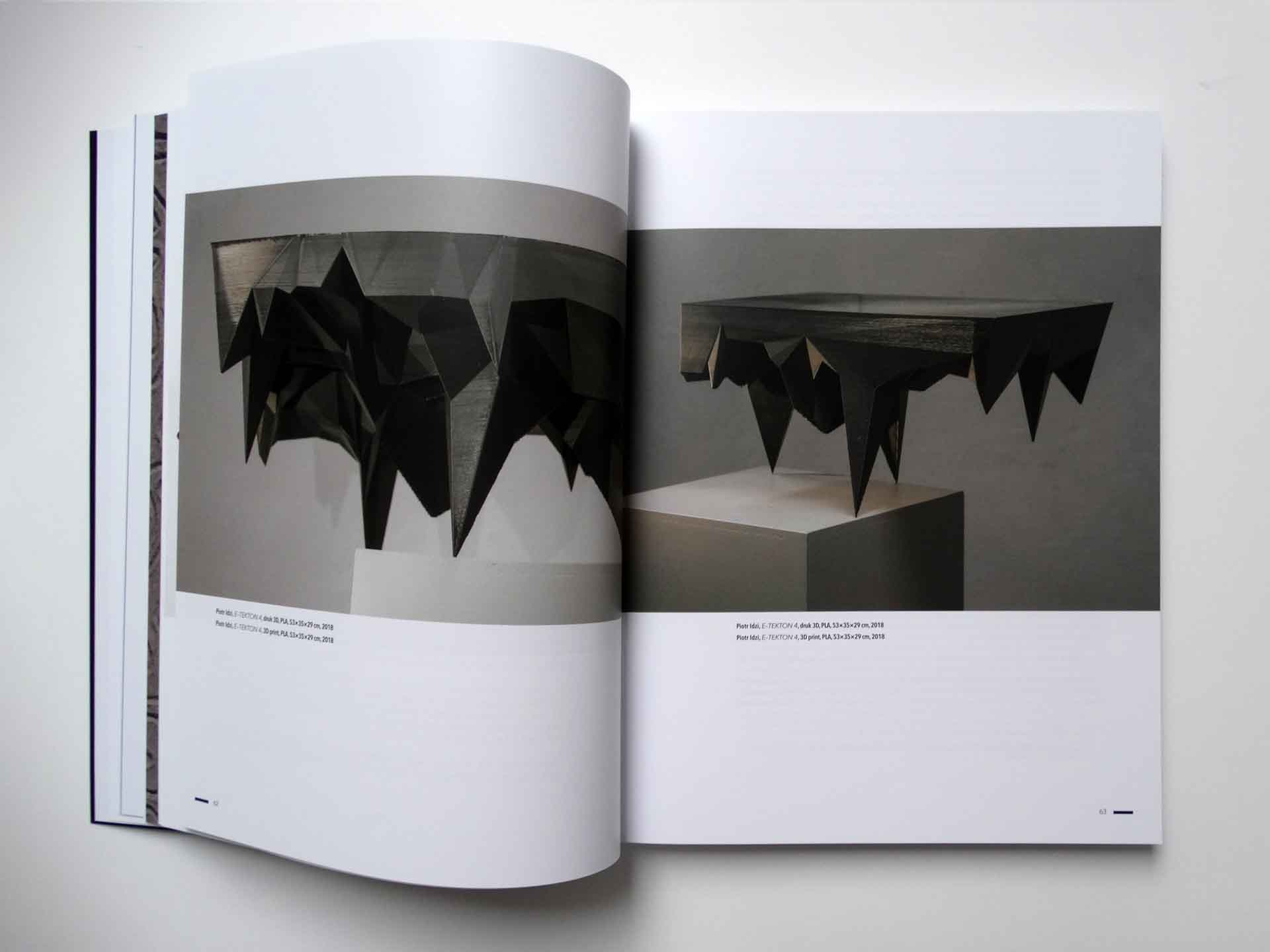

![Monika Aleksandrowicz Art book PANDEMICAL DIARY 3.0 _ ASEMIC WRITING [11.2021-10.2022], size- 210 x 130 mm, 160 pages 141](https://artebuena.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Monika-Aleksandrowicz-Art-book-PANDEMICAL-DIARY-3.0-_-ASEMIC-WRITING-11.2021-10.2022-size-210-x-130-mm-160-pages-141.jpg)

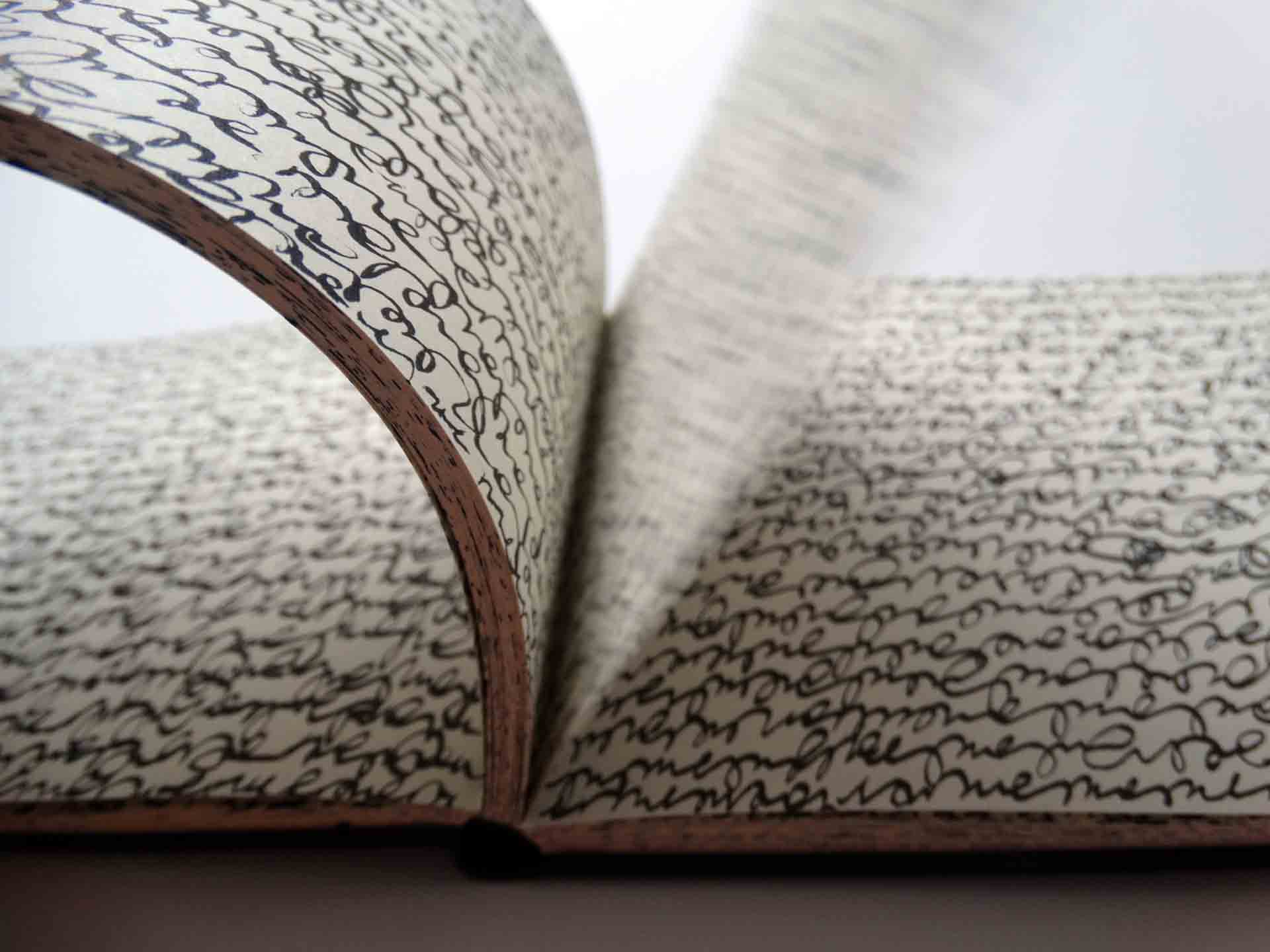

![Monika Aleksandrowicz Art book PANDEMICAL DIARY 3.0 _ ASEMIC WRITING [11.2021-10.2022], size- 210 x 130 mm, 160 pages 169](https://artebuena.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Monika-Aleksandrowicz-Art-book-PANDEMICAL-DIARY-3.0-_-ASEMIC-WRITING-11.2021-10.2022-size-210-x-130-mm-160-pages-169.jpg)

SEMIOGRAPHY. A Visual Experiment at the Intersection of Sign, Language, and Perception

Introduction

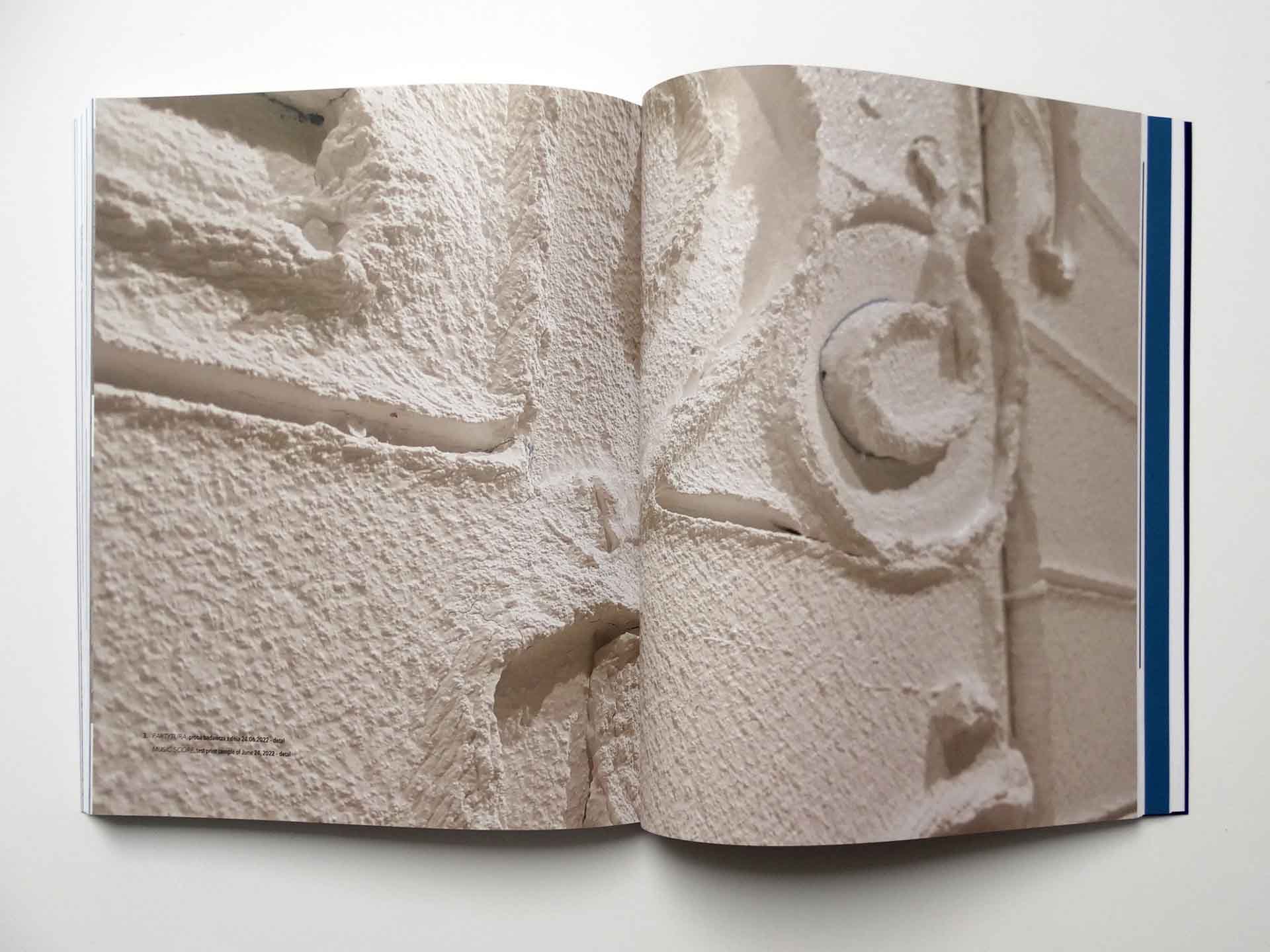

Contemporary art increasingly operates at the borders of language, communication, and perception, testing their elasticity and capacity for redefinition. One example of such a practice is my original cycle Semiography – an artistic and research project that has evolved since 2010 into a multilayered visual discourse, rooted in asemic practice, semiotic reflection, and experimentation with the artist’s book.

Semiography is a space of creative in-betweenness: between letter and sign, between meaning and its absence, between the movement of the hand and the structure of language. This text offers an analytical and theoretical perspective on the cycle, treating it as a laboratory of form and meaning, but also as an ongoing project that redefines itself through writing practices, publication, performative action, and research on visual perception.

1. Context: From Sign to Asemia

The inspiration behind the Semiography cycle was the need to step beyond known linguistic systems and enter a space that Umberto Eco referred to as the „open work”—a potential, dynamic, and indeterminate structure whose interpretation depends on the viewer¹. Instead of constructing stable messages, Semiography produces signs without fixed semantics which, despite their apparent legibility, resist unequivocal translation.

In this sense, the project aligns with the tradition of asemic writing but simultaneously transcends it by incorporating mathematical, rhythmic, spatial, and even performative elements. The sign is no longer an information carrier, but a gesture, a trace, a situation – a transitional, often fleeting entity.

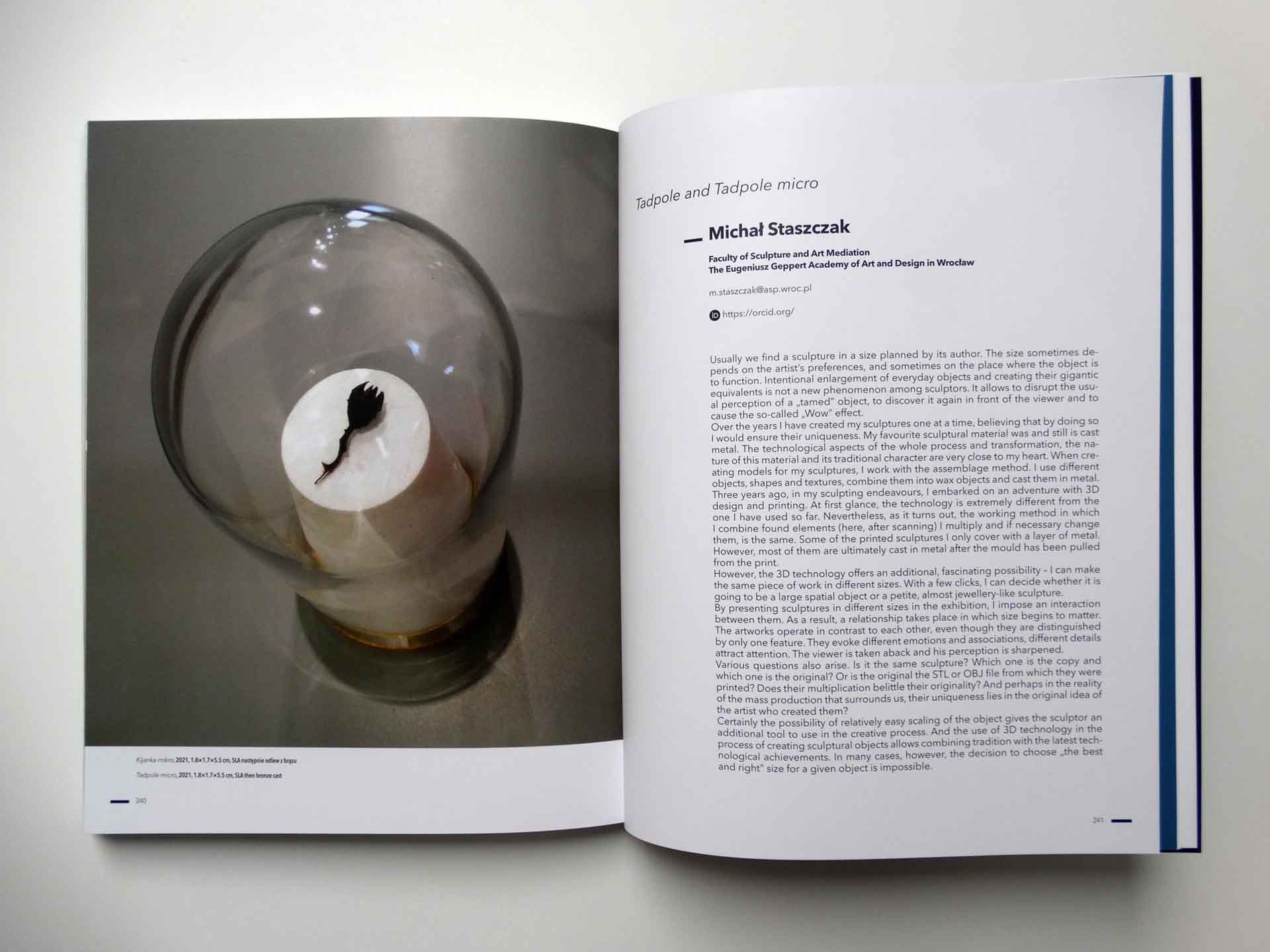

2. Semiography as an Artist’s Book

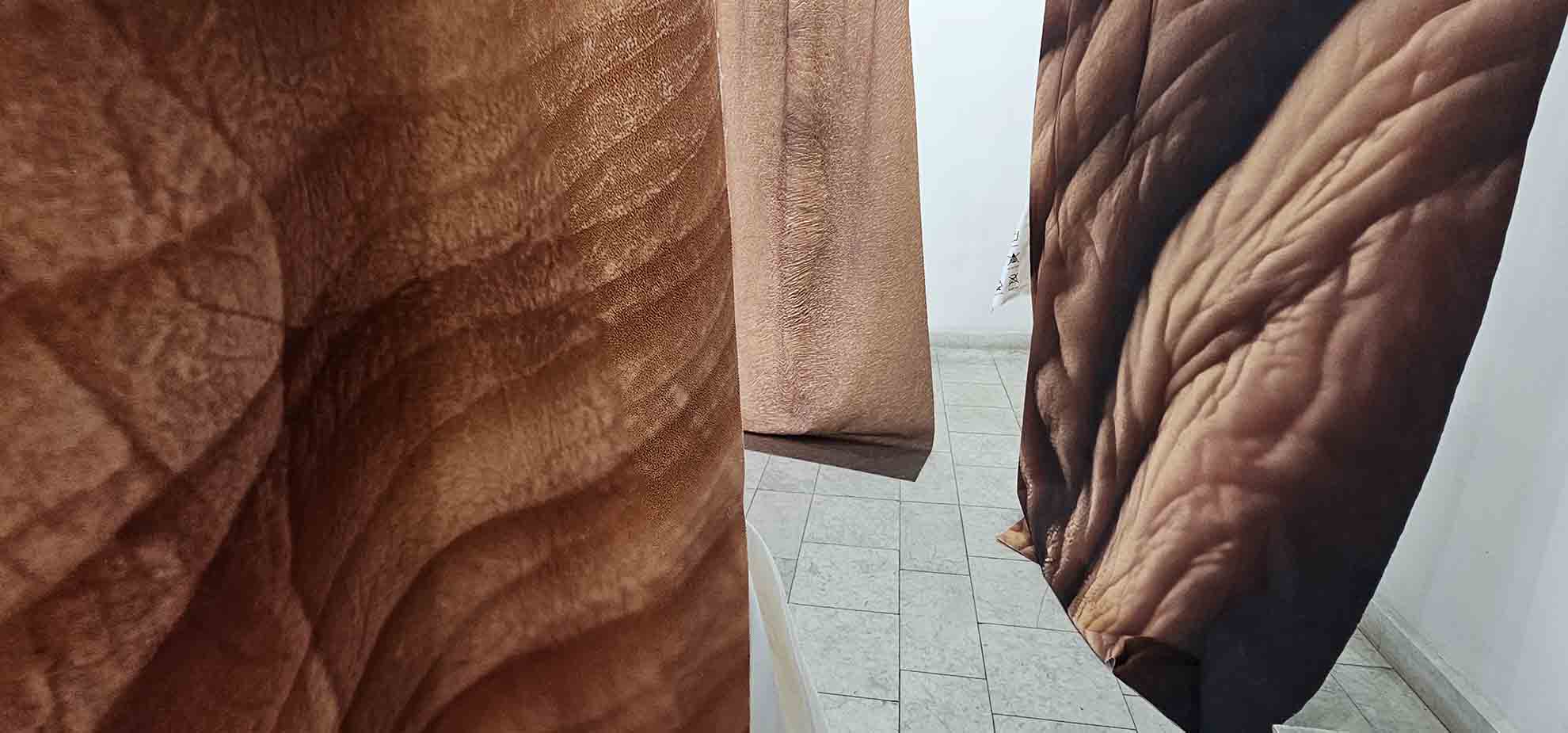

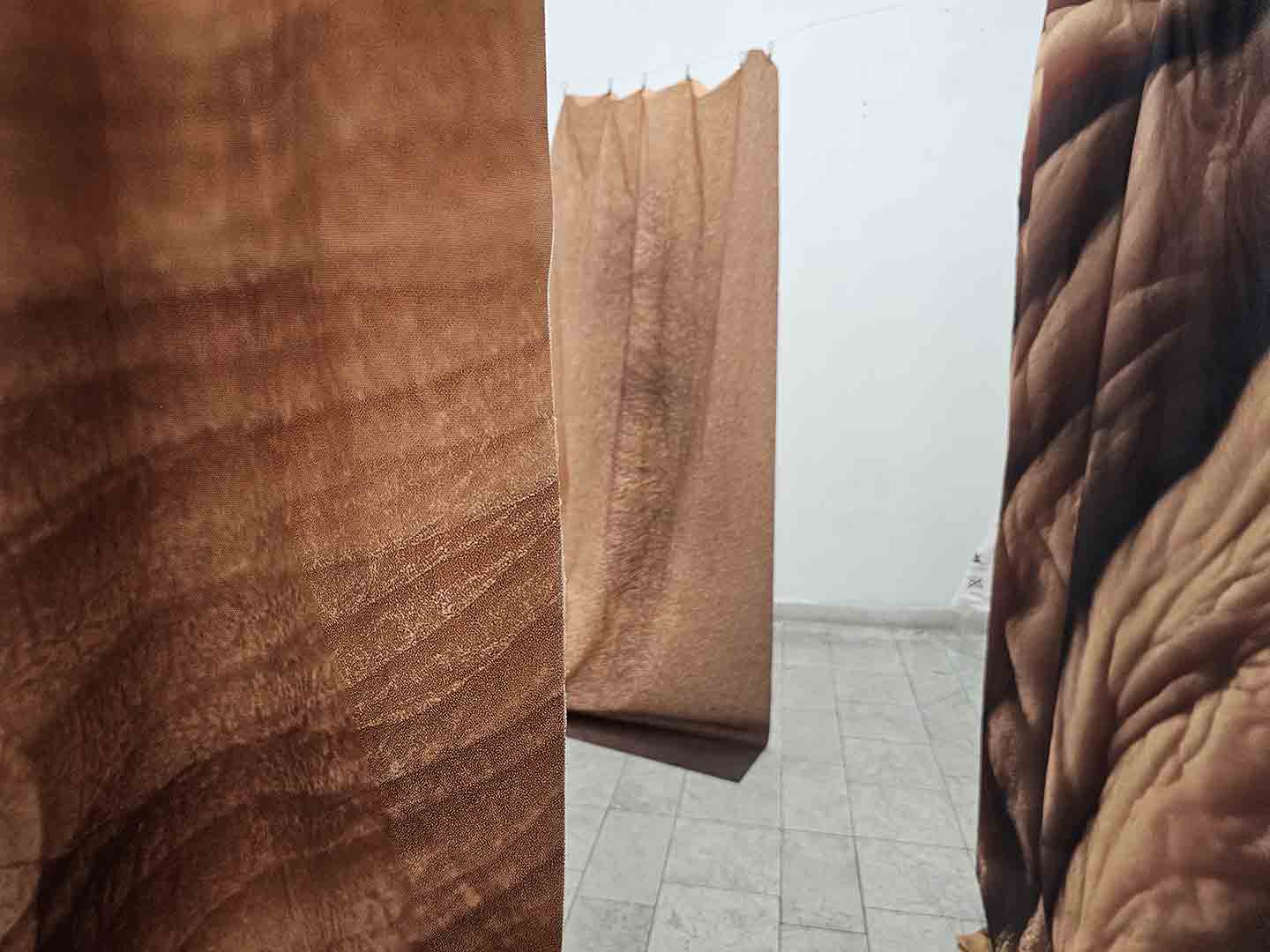

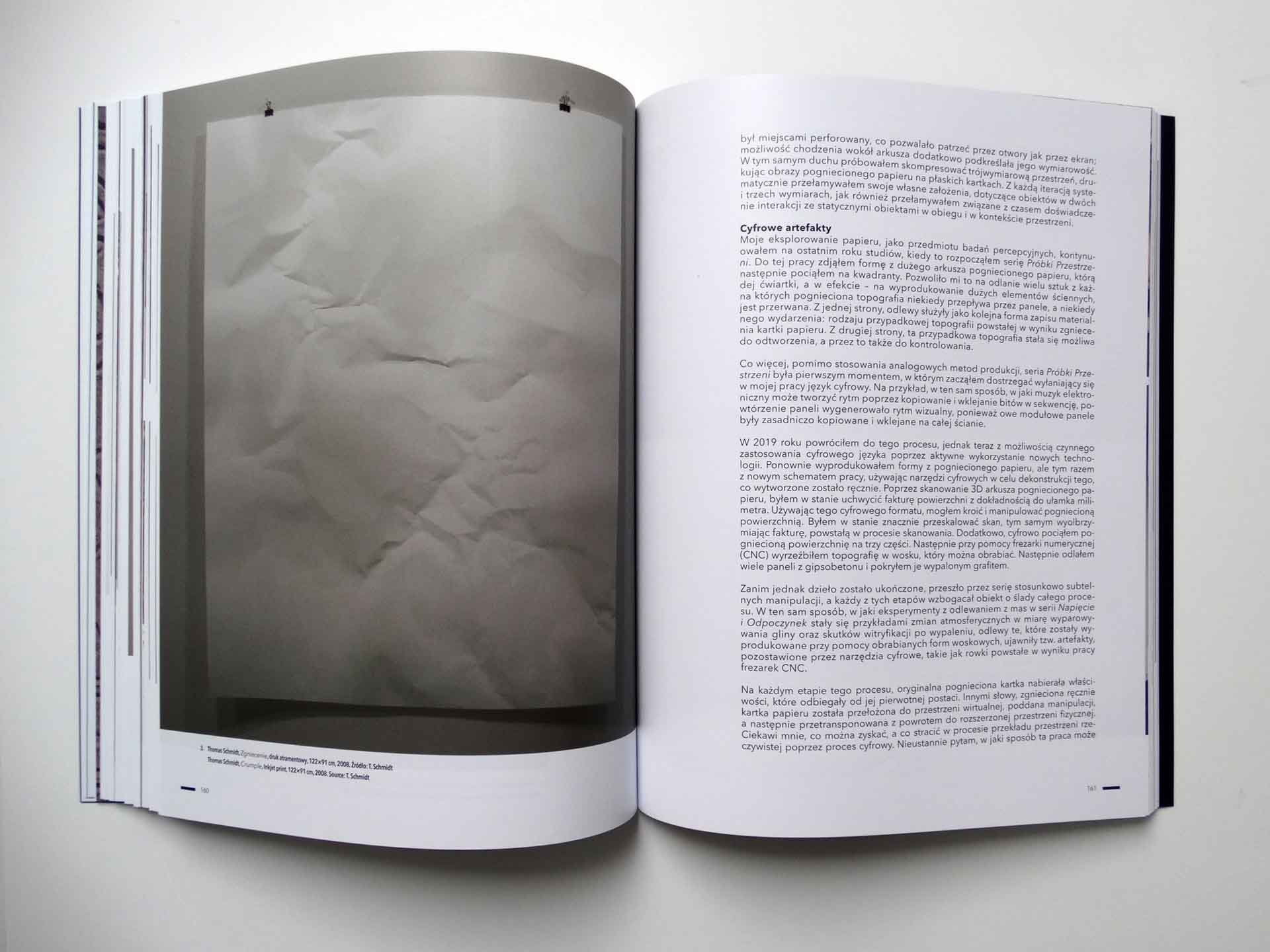

An early development in the cycle was the artist’s book generating visual modifications – a format that assumes active co-creation by the viewer. The publication becomes an open medium, responsive to how it is viewed, exposed to light, folded, or manipulated in space.

In my doctoral dissertation titled The Artist’s Book Generating Visual Modifications, I described the methodology for creating such objects, emphasizing their processual and interactive nature. Semiographic books are not just carriers of content but tools for exploring the relationship between sign and perception. Their structure resembles an optical apparatus – a system of mirrors, filters, and illusions – while remaining grounded in the rhythm of the hand and the materiality of paper.

3. The Interpretative Paradox and the Aphasia of Meaning

One of the central themes of Semiography is the so-called interpretative paradox – the moment when a sign suggests meaning but cannot be reduced to any specific interpretation. In this space, the sign does not so much communicate as it exposes the act of communication itself – its tensions, fractures, and dispersions².

This is an area close to aphasia – not as a speech disorder, but as a creative potential. Semiography does not imitate language but deconstructs its components, revealing how easily meaning can be simulated or annulled. In this way, one can speak of an „aesthetics of uncertainty”—a tension between expectation and its suspension, between structure and chaos, rhythm and its collapse.

4. Phases in the Development of the „Semiography / Semiografia” Cycle

Phase I (2010–2015): Glyphs and the Study of Asemia

Initial works focused on developing a personal graphic alphabet – a set of glyphs without assigned meanings. These signs resembled calligraphy, foreign scripts, or mathematical notation, but were entirely asemic.

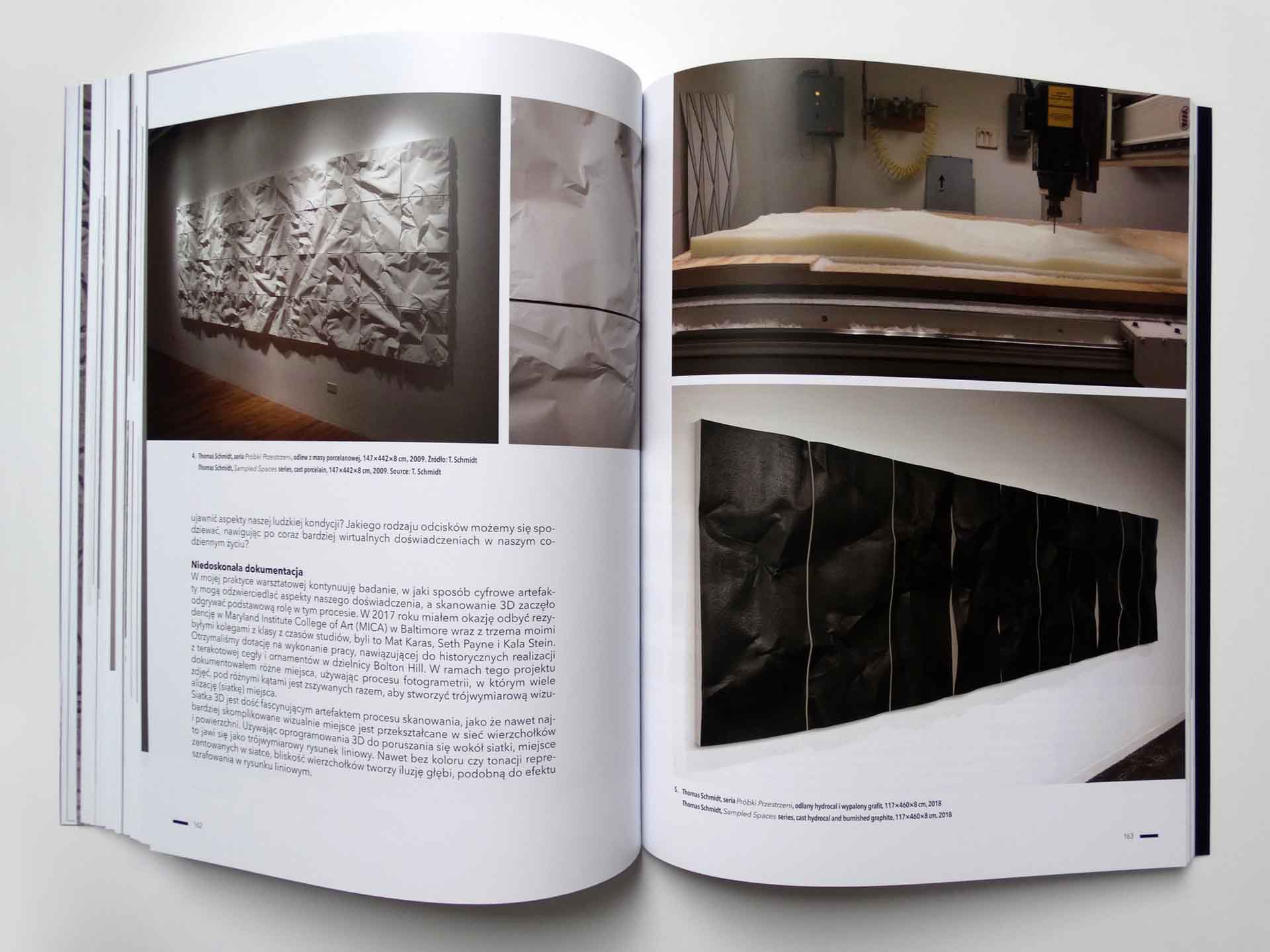

Phase II (2015–2020): Semiography 1.0 / 2.0 – The Book as a Variable Medium

This period saw the creation of experimental publications – artist’s books whose layout changed depending on light, browsing technique, or spatial configuration.

Phase III (2020–2023): Rhythm, Performance, Emotion

Notations became a form of asemic diary – a record of bodily states, muscle tension, and states of awareness. The sign became an emotional trace – a blend of automatism and mindfulness, action and meditation.

Phase IV (2023–2025): Interdisciplinarity and Structure

Recent works deepen the dialogue with geometric rhythm, the golden ratio, topology, construction, and formal structure rooted in mathematical order.

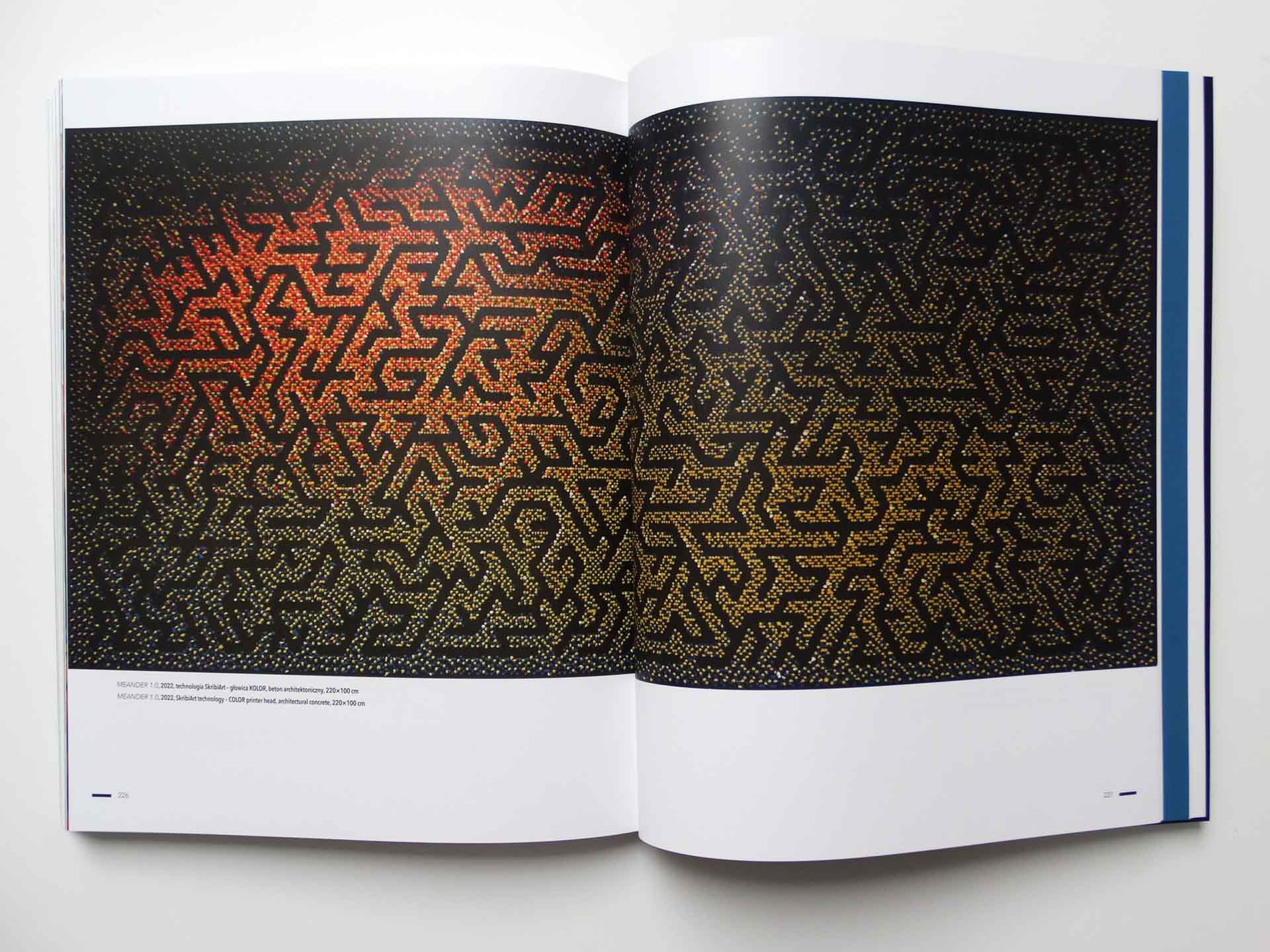

5. Semiography in Relation to Mathematics and Rhythm

The Semiography cycle develops in close relation to rhythm and mathematical structures, which do not play an illustrative role but form the internal order organizing the sign and its extension in time and space.

In this context, mathematics is not a rigid system but a potential language that, like the asemic sign, operates on the border of abstraction and intuition. Rather than communicating a specific content, it structures thought and perception³.

6. Philosophical Contexts: Deleuze, Barthes, Eco, Kristeva, Agamben

Deleuze’s concept of the diagram and deterritorialization of meaning allows us to view Semiography as a field of forces⁴. Barthes inspires the notion of the text as an open structure composed of quotations and gaps⁵. Eco provides the theory of the open work and semiotic processes that perfectly frame Semiography as a dynamic structure⁶. Kristeva reveals the relationship between the pre-conscious matter of language and its surface⁷. Agamben, in turn, enables an understanding of the sign as a potential act that may or may not be actualized⁸.

7. Semiography as a Cognitive Tool. Between Insight and Gesture

In the Semiography project, the sign ceases to be merely a communicative element. It becomes a tool of cognition – not only of the external world but also of the internal realms: mind, emotion, structures of perception. This is cognition that does not proceed through conventional language but through gesture, rhythm, hand tension, repetition, error, and meditative focus on structure.

The sign functions like a laboratory object – created, destroyed, modified repeatedly – not to convey, but to reveal mechanisms of interpretation. Semiography thus becomes a phenomenology of gesture – mapping unconscious trajectories of the sign, creating a new semantic field.

Conclusion: Semiography as a Practice of Liminal Space

The Semiography cycle can be seen as an ongoing practice on the threshold: between sign and non-sign, between language and corporeality, between cognition and its suspension. It is a form of liminal art – operating in a space of transition, indeterminacy, dynamism. In this space – neither already linguistic nor fully visual – emerges a new form of communication: intense, intuitive, performative.

As an artist, researcher, and author of the project, I perceive Semiography not only as a series of works but as a method of reflecting on the very process of thinking and meaning-making. It is a tool of insight – both theoretical and somatic. In a world oversaturated with messages, Semiography offers a practice of silence, ambiguity, and attention.

¹ Umberto Eco, The Open Work, trans. A. Cancogni, Harvard University Press, 1989.

² Roland Barthes, The Rustle of Language, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

³ Jakub Jernajczyk, „Art Inspired by Mathematics”, „Format” no. 82–83, 2011.

⁴ Gilles Deleuze, Foucault, trans. S. Hand, University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

⁵ Roland Barthes, Image – Music – Text, New York: Hill and Wang, 1977.

⁶ Umberto Eco, The Role of the Reader, Indiana University Press, 1979.

⁷ Julia Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language, New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

⁸ Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Pismo asemiczne – Gest poza znaczeniem

Analiza naukowa eksperymentów językowo-wizualnych Moniki Aleksandrowicz

- Wprowadzenie – od pisma do rysunku

W twórczości Moniki Aleksandrowicz pismo asemiczne jawi się jako kluczowa strategia dekonstrukcji założeń dotyczących czytelności, autorstwa i komunikacji. Prace asemiczne funkcjonują na pograniczu pisma i rysunku, znaku i abstrakcji, języka i obrazu. Przywołują strukturę zapisu, lecz odmawiają jej funkcji użytkowej. Te inskrypcje — często oparte na pulsujących rytmach, symbolicznych znakach i gestualnych śladach — odrzucają semantyczną jednoznaczność, oferując zamiast niej spotkanie z czystą formą jako potencjalnym językiem.

- Poza językiem – poetyka niewyrażalnego

Pismo asemiczne, zgodnie z definicją, oznacza „pismo bez znaczenia”. Jednak w interpretacji Aleksandrowicz nie chodzi o brak znaczenia, lecz o radykalną otwartość na wiele możliwych interpretacji. Dzieła te konfrontują odbiorcę z jego lingwistycznymi przyzwyczajeniami, wprowadzając go w stan zawieszenia semantycznego — stan, w którym interpretacja jest możliwa, ale nieosiągalna. Ten gest przypomina fenomenologiczną koncepcję epoché – zawieszenie sądu, które pozwala skupić uwagę na samych warunkach powstawania znaku.

- Ręka, która pisze – ciało w śladzie

Dzienniki asemiczne oraz pojedyncze kompozycje Moniki Aleksandrowicz są głęboko ucieleśnione. Gest ręki, zmienność nacisku, rytmu i ruchu – wszystko to zapisuje obecność ciała artystki jako myślącego i odczuwającego podmiotu. Ten somatyczny wymiar nadaje śladowi wizualnemu charakter afektywny i czasowy. W tym kontekście prace można czytać zarówno przez pryzmat koncepcji André Leroi-Gourhana o geście jako zapisie kulturowym, jak i w duchu Viléma Flussera, który traktował „gest pisania” jako fundamentalny akt kulturowy.

- Czasowości powtórzenia – pismo asemiczne jako praktyka

W długoterminowej praktyce prowadzenia asemicznych dzienników, Aleksandrowicz nadaje powtórzeniu rangę estetycznego i poznawczego narzędzia. Nie jest to powtórzenie mechaniczne – każda strona rejestruje mikro-różnicę: zmianę napięcia emocjonalnego, poziomu skupienia, obecności ciała. W czasie praktyka ta przekształca się w mapę stanów uwagi, rodzaj pisma bez słów, przypominającego zarazem automatyczne pisanie, jak i zenistyczną kaligrafię – z tym, że pozbawioną narracji duchowej. To sztuka obecności.

- Nieczytelność jako opór – polityczny wymiar nieczytelnego

W świecie przesyconym znakami, ikonami, komendami i sloganami, pismo asemiczne Aleksandrowicz przywraca przestrzeń ciszy wśród hałasu. Odmowa bycia czytelnym staje się tu formą oporu wobec instrumentalizacji, klasyfikacji i zawłaszczenia. To poetyka nieprzejrzystości w epoce przejrzystości i algorytmicznej czytelności. Tym samym prace wpisują się w poststrukturalistyczną i feministyczną krytykę języka – gdzie nieczytelność staje się nie deficytem, ale strategią przetrwania i autonomii.

- Posttekstualny interfejs – między książką a interfejsem

Dzieła asemiczne często przyjmują formy zbliżone do książek lub układów sekwencyjnych, przywołujących linearną strukturę zapisu. Jednak „książki” te są nieczytelne – przekształcają kodex w interfejs kontemplacji estetycznej, a nie narzędzie pozyskiwania informacji. Tym samym twórczość Aleksandrowicz podejmuje dialog z teoriami posttekstualności, hipertekstu oraz interfejsu jako przestrzeni negocjacji pomiędzy autorem, czytelnikiem i maszyną.

Wnioski

Praktyka asemiczna Moniki Aleksandrowicz to złożona i wielowarstwowa medytacja nad tym, czym jest pisanie, czytanie i znaczenie. Nie jest to jedynie gest formalny czy estetyczny, ale głęboka filozoficzna refleksja realizowana środkami wizualnymi. Pismo asemiczne artystki kreśli kontury porażki języka i jego wolności – wyznaczając przestrzeń, w której myśl staje się gestem, a cisza formą innego mówienia.